Different Spanish Accents from Around the World

Spanish is the second most spoken language in the world with more than 460 million people native speakers. With such a far reach, it’s no surprise that this popular language is incredibly diverse. While there’s no “best accent” or dialect, it’s helpful to know about what to expect when visiting another country. Today, we will be talking about some of the ways Spanish varies in different regions around the world.

Looking for how to type Spanish accents? We cover how to do that on Apple MacOS and iOS here.

One could say that there are as many ways of speaking a language as there are speakers, but still, many trends can be found among members of the same generation, the same occupational field, gender, ideology, and, of course, among people who live in the same region.

The variety of language spoken in a particular geographical area is usually called a dialect and, as boundaries between regions are indefinite, there are several ways of distinguishing them. I’ll stick to the classification proposed in this book to focus on the major Spanish dialects. We will be paying attention to the differences in pronunciation, in the way the language is used, and in the distinctive words found in each region. Bear in mind that within each dialect, tons of variations can be identified.

Spanish Accents in Spain

Spanish is only one of the many languages that are spoken in Spain. It became the most widely spread throughout the country as a result of the centralist politics carried out by the Franco dictatorship, which forbade the use of any language other than Spanish for almost 40 years. All these other languages that were once prohibited, such as Catalan, Basque, Galician, Aranese, Asturian, Aragonese, and Valencian, are now recognized by the Constitution. But Spanish is still the most spoken language in the area with more than 42 million speakers. In this country, we can find three major dialects.

First and Second Languages of Spain

Spanish (Castilian), spoken by about 99% of Spaniards as a first or second language. Catalan (or Valencian) is spoken by 19%, Galician by 5%, and Basque by 2% of the population. Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Languages_of_Spain

Castilian Spanish

Here we will use the term Castilian to refer to the Spanish dialect spoken in the north of Spain. Bear in mind that this same term can also be used to refer to the Spanish language itself as a way to state that there are other languages that are spoken in Spain. The Castilian dialect has two main variations: Manchegan Castilian in Castilla-La Mancha and Northern Castilian to the north of Madrid.

Pronunciation

- Pronouncing the letters S and Z differently. The letter Z sounds somehow similar to TH in English. When the letter C is followed by an E or I, it acquires the same sound.

- casa ≠ caza

- Sena ≠ cena

- sima ≠ cima

Castilian Spanish S – Z Sound Example

Marina from Notes in Spanish

Listen to the audio and notice how Marina pronounces differently the letters S and Z in the words montañosa and naturaleza.

- Pronouncing the sound of the letter J, which we also found in the syllables GE and GI, as a hard H in English. In most dialects, this sound is softer.

- jardín

- gemelo

- gigante

- Dropping the D sound in between vowels, especially in the ending -ado.

- cansado → cansao

- estudiao → estudiado

- hablado → hablao

- Turning the CS sound into S. This happens mainly in the rural areas.

- sexy → sesy

- taxi → tasi

- Pronouncing LL as Y. This phenomenon is called yeísmo. Only in regions that are in touch with Catalan, as well as in some rural areas of Castilla León and Castilla-La Mancha, LL preserves its distinctive sound.

- llama = yama

- halla = haya

- llena = yena

Use

- The pronoun tú is used as an informal you, to express closeness and familiarity.

- The pronoun vosotros is used as an informal plural you, together with the corresponding pronoun os when necessary.

- Vosotros sois mi familia.

- Os voy a decir algo muy importante.

Spanish Use of “Os” Example

Marina from Notes in Spanish

Marina says the pronoun os twice. Can you identify it?

- Present perfect is used to talk about the recent past, except in Galicia, the western parts of Asturias and Leon. This is one of the biggest differences between Spanish from Europe and Spanish from America, as in America preterit tense is used instead.

- Spain: Esta mañana he tenido un accidente.

- America: Esta mañana tuve un accidente.

Castilian Spanish Use of Present Perfect Example

Marina from Notes in Spanish

Marina uses the present perfect to talk about the recent past when she says “… hemos venido a caminar por la montaña…“

- Infinitive is used as imperative.

- ¡Venid aquí! → ¡Venir aquí!

- Imperfect and pluperfect subjunctive use the ending -se.

- Imperfect: hablara → hablase

- Pluperfect: hubiera hablado → hubiese hablado

- The pronoun le is sometimes used instead of lo or la, especially when it refers to a man. This is called leísmo de persona.

- Ayer vi a Juan y lo invite a la fiesta. → Ayer vi a Juan y le invite a la fiesta.

It is also used instead of les.

- Les dije a mis amigos que no puedo ir. → Le dije a mis amigos que no puedo ir.

This last one is considered to be an incorrect use of the language, as well as using le to refer to a feminine noun or to a thing, but it happens.

- The pronoun la is often used instead of le when it refers to a woman, especially in Castilla and Leon, in Madrid and its area of influence. This is called laísmo and is considered to be an incorrect use.

- Le regalé flores a María. → La regalé flores a María.

- Not very common, but sometimes the pronoun lo replaces le when it refers to a man, mainly in rural areas of Castilla and Leon. This is called loísmo and is also considered incorrect.

- Le llamé a Pedro. → Lo llamé a Pedro.

Vocabulary

In Castilian Spanish we find words that are unique to this dialect and are hardly used by the rest.

- Everyday Castilian words:

- piso: apartment.

- Suelo: floor, not piso.

- Coche: car, not carro.

- Ordenador: computer.

- Albornoz: bathrobe.

- Calcetín: sock.

- Gamba: shrimp.

- Zumo: juice.

- Slang:

- Chaval, chavala: guy.

- Molar: to like.

- Follón: problem, conflict.

Castilian Spanish Slang Example

Marina from Notes in Spanish

Andalusian Spanish

Andalusian Spanish is found in the south of Spain and spreads out beyond Andalusia. Here we can distinguish four main regions: Extremadura, Western Andalusia (Huelva, Cadiz, Seville, and Cordoba), Eastern Andalusia (Jaen, Malaga, Granada, Almeria), and Murcia.

Pronunciation

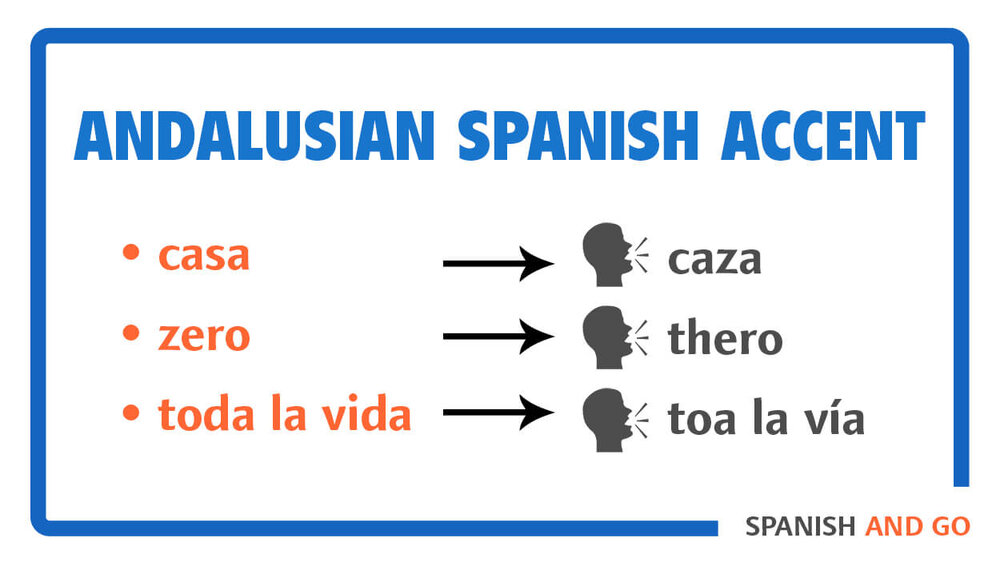

- Pronouncing Z like an S, as well as the letter C when followed by an E or an I. This is called seseo.

- casa = caza

- Sena = cena

- sima = cima

Nevertheless, in Jaén, Almería, the eastern part of Granada, and in some parts of the Castelan-Andalusian border in the north of Córdoba and in the north of Huelva, S and Z keep their distinctive sound. In the south of Andalucía and Almería, on the other hand, people do the exact opposite: they pronounce the letters Z and S and the syllables CE and CI with the sound of a Z. This is called ceceo.

- sí → thi

- cero → thero

- cielo → thielo

- Aspirating the S when it is located at the beginning of a syllable.

- señora → heñora

- bolsa → bolha

- cosa → coha

When this sound is in between two vowels, it even disappears.

- casa → caha, cáa

- así → ahí, aí

- mesa → meha, mea

- Softening the CH sound, pronouncing it as SH. Doing this depends on the context and is avoided by high-status groups.

- muchacha → mushasha

- ocho → osho

- mucho → musho

- Dropping the D sound in between vowels.

- toda la vida → toa la vía

- cantado → cantao

- bebido → bebío

- The sound of the letter J and the syllables GE and GI is soft, like an H in English.

- cajón → cahón

- geranio → heranio

- girasol → hirasol

- Turning the L into an R or the R into an L when they are located at the end of a syllable.

- el caldito → er cardito

- por detrás → pol detrás

When these letters are at the end of a word, they are just dropped.

- papel → papé

- cantar → cantá

The R sound also disappears when it is followed by an L or an N.

- perla → pela

- carne → cane

Like R and L, the N and D sounds are also dropped if they are at the end of a word.

- aman → ama

- usted → usté

- Yeísmo: pronouncing LL as Y.

- llama = yama

- halla = haya

- llena = yena

Andalusian Spanish Example

Vicente from Spanish with Vicente

Use

- The pronoun tú is used as an informal you, to express closeness and familiarity.

- The pronouns vosotros and ustedes are both is used as a plural you. Vosotros is more common in Western Andalusia, especially with friends and family.

- Also in Western Andalusia, the pronoun se is used instead of os.

- ¡Os vais a caer! → ¡Se vais a caer!

- Infinitive is used as imperative for ustedes or vosotros. They don’t even change the pronoun when there is one.

- ¡Sentaos! → ¡Sentarse!

- ¡Callaos! → ¡Callarse!

- Present perfect is used to talk about the recent past.

- Spain: Esta mañana he tenido un accidente.

- America: Esta mañana tuve un accidente.

- Some nouns acquire the opposite gender.

- el sartén → la sartén

- el calor → la calor

- Placing a definite article before someone’s name. This also happens in regions that have contact with Catalan and also in Chile.

- ¿Ya hablaste con la Lola?

- El Pedro no está aquí.

- To sound more polite, the pronoun le takes the place of lo or la when it refers to a person. This is called leísmo de cortesía.

- ¿Lo/La puedo ayudar? → ¿Le puedo ayudar?

Vocabulary

These are some of the words that are characteristic of Andalusian dialect.

- Archaisms:

- cabero: last one.

- casapuerta: entrance hall.

- entenzón: fight.

- escarpín: sock.

- fuéllega: trace, footprint.

Some of these archaisms have a Mozarab origin:

- almatriche: irrigation canal.

- cauchil: tank.

- paulilla: clothes moth.

- Slang:

- búcaro: pitcher.

- bulla: hustle and bustle.

- descocado: very clean.

- gabarra: annoyance.

- hambrina: extreme hunger.

- malaje: charmless, graceless person.

- porcachón: dirty person.

- relente: dew.

- The expression ¡ozú! And its variants ¡ofú!, ¡ohú!, and ¡ojú! to show surprise, annoyance, astonishment, irritation…

- We can also hear words that come from Caló language, spoken by the Spanish and Portuguese Romani.

- hartible: annoying.

- jurón: an extremely lazy person.

- esmayao: someone who is really hungry.

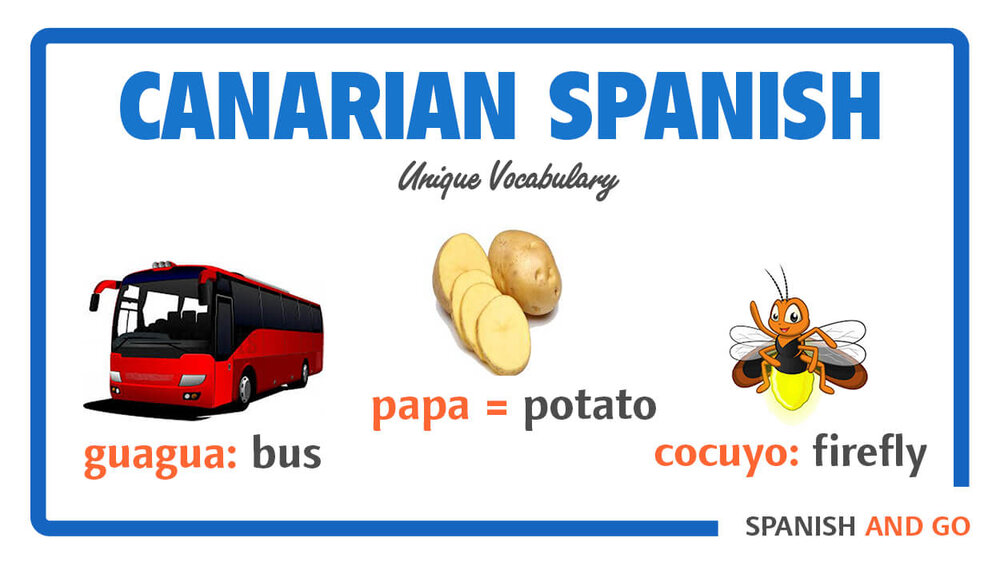

Canarian Spanish

Canarian Spanish is spoken throughout the Canary Islands. This dialect has a lot of things in common with Andalusian because the people who arrived to the archipelago came mostly from Seville, Jerez and Cadiz. Nevertheless, in spite of this connection, Canarian Spanish has evolved independently from its Andalusian predecessor, acquiring over time characteristics of its own.

Pronunciation

- Seseo: pronouncing Z like an S, as well as the letter C when followed by an E or an I.

- casa = caza

- Sena = cena

- sima = cima

- Aspiration of the S when it is located at the end of a syllable.

- buenos → buenoh

- muchas → muchah

- más → máh

- Dropping the D sound in between vowels, especially in rural areas.

- toda la vida → toa la vía

- cantado → cantao

- bebido → bebío

- The sound of the letter J and the syllables GE and GI is soft, like an H in English.

- cajón → cahón

- geranio → heranio

- girasol → hirasol

- Pronouncing LL and Y differently, but only elders do this.

Use

- The pronoun tú is used as an informal you, to express closeness and familiarity.

- The pronoun ustedes is used as a plural you. In La Gomera, El Hierro, and La Palma vosotros is also used.

- Present perfect is used to talk about the recent past.

- Spain: Esta mañana he tenido un accidente.

- America: Esta mañana tuve un accidente.

- Some very specific changes take place.

- para que tú entiendas → para tú entender

- hace más de cinco años → hay más de cinco años

- cual → cualo

Vocabulary

American influence can be found in the vocabulary that is typical of this dialect. Also, the indigenous language Guanche is still present although its population is now considered extinct.

- Americanisms:

- guagua: bus.

- papa instead of patata.

- guayabera: Caribean shirt.

- cocuyo: firefly.

- Guanche:

- tabaiba → a type of tree

Spanish Accents in the Americas

With the colonization of America at the hands of Europeans, the Spanish language got richer as it received a strong influence from the indigenous languages that are spoken in this continent.

Caribbean Spanish

Caribbean Spanish has more things in common with the Andalusian and Canarian dialects than with Castilian, probably because the Canary Islands were a transit point to America where ships stuck up on trading goods during the colonial period and this contributed to the migration of people from the south of the Iberian Peninsula to America, especially to Cuba and Venezuela.

This dialect is composed of Antillean Caribbean (Cuba, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico) and Continental Caribbean (Caribbean coast of Mexico, Honduras, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, and Venezuela).

Puerto Rican Spanish Example

Fernando Ufret

Pronunciation

Caribbean Spanish Aspiration of the S Example

Mariela from Mariela in Spanish

- Seseo: pronouncing Z like an S, as well as the letter C when followed by an E or an I.

- casa = caza

- Sena = cena

- sima = cima

- Aspiration of the S when it is located at the end of a syllable.

- buenos → buenoh

- muchas → muchah

- más → máh

Listen and pay attention to the sound of the S in the following words:

- mi nombre es

- profesora de español

- lo que más me gusta

- Softening the CH sound, pronouncing it as SH, in certain areas of Puerto Rico and urban regions of Venezuela.

- muchacha → mushasha

- ocho → osho

- mucho → musho

- Dropping the D sound in between vowels.

- toda la vida → toa la vía

- cantado → cantao

- bebido → bebío

- The sound of the letter J and the syllables GE and GI is soft, like an H in English.

- cajón → cahón

- geranio → heranio

- girasol → hirasol

- Widening vowels as a result of the aspiration of the S. This happens in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Dominican Republic.

- pescado → pehcáo

- tostado → tohtáo

- vestida → vehtía

- Dropping consonants, mainly L, R, N, and D, if they are located at the end of a word.

- papel → papé

- cantar → cantá

- aman → ama

- usted → usté

- When a word ends in N, the previous vowel acquires a nasal sound. Sometimes the consonant is dropped, especially in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Dominican Republic.

- pan → pa

- Turning the rolled R into a hard H in some areas of Puerto Rico.

- carro → caho

- perro → peho

- arriba → ahiba

- Turning R into an L when it is placed at the end of a syllable. This phenomenon is called lambdacism and happens in Puerto Rico and in Dominican Republic, in the area close to Santo Domingo.

- Puerto Rico → Puelto Rico

- arte → alte

- surfear → sulfeal

In the north of Dominican Republic, instead of turning the R into an L, it is turned into an I, and in the southeast, it is just dropped. This is associated with low-status groups.

- carne → caine, cane

- porque → poique, poque

- parque → paique, opaque

- Yeísmo: pronouncing LL as Y.

- llama = yama

- halla = haya

- llena = yena

IN THIS VIDEO, LISTEN TO MORE EXAMPLES OF CARIBBEAN SPANISH, MEXICAN SPANISH, COLOMBIAN SPANISH, PERUVIAN SPANISH, AND MORE.

Use

- The pronoun tú is used as an informal you to express closeness and familiarity.

- The pronoun ustedes is used for plural you. Only in two little regions of the east of Cuba, the pronoun vos is used.

- Preterite is used to talk about the recent past, which is definitively one of the main differences between American Spanish and European Spanish.

- America: Esta mañana tuve un accidente.

- Spain: Esta mañana he tenido un accidente.

- The subject pronoun is explicit and it is placed right before the verb. This happens especially when asking questions and when using a verb in the infinitive.

- ¿Qué tú quieres?

- Le pedí dinero prestado para yo no preocuparme.

- The preposition de is dropped with verbs that require to be followed by de que. This is called queísmo and is considered an incorrect use of the language.

- Me di cuenta de que no traje mis llaves. → Me di cuenta que no traje mis llaves.

- Estaba seguro de que vendrías. → Estaba seguro que vendrías.

- Adding a final N when the plural form of the imperative ends with a pronoun. This is associated with low-status groups.

- váyanse → vayansen

- espérense → espérensen

- apúrense → apúrensen

- Leísmo de cortesía: to sound more polite, the pronoun le takes the place of lo or la when it refers to a person.

- ¿Lo/La puedo ayudar? → ¿Le puedo ayudar?

- Using present continuous to express future.

- En diez minutos estoy llegando.

- Turning impersonal verb haber into plural.

- Había muchas personas. → Habían muchas personas.

- Hubo muchos problemas. → Hubieron muchos problemas.

- Some nouns acquire the opposite gender.

- la sartén → el sartén

- el pijama → la piyama

WE GO IN-DEPTH ABOUT THE PUERTO RICAN ACCENT IN THIS ARTICLE.

Vocabulary

Besides receiving influence from the indigenous language of this region, Taino, Caribbean Spanish adopted some characteristics from the languages spoken by the African population.

- Taino:

- boricua: inhabitant of Boriquén, the island where we now find Puerto Rico.

- ají: pepper.

- batata: sweet potato.

- canoa: canoe.

- iguana

- jaiba: crab.

- manatí: manatee.

- yuca: yucca.

- African:

- banana

- champola: a type of drink.

- ñame: yam.

- cheche: a brave person.

- sanaco: silly, naive.

- chango: a type of monkey.

- quimbombó: a type of monkey.

- yaya: a type of tree.

- bachata: a type of dance, party.

- conga

- mambo

- marimba

Venezuelan Spanish Slang Example

Mariela from Mariela in Spanish

Mexican and Central American Spanish

Dialectal division is particularly complex in this area, not only because of the great territorial extension, but also due to the presence of a wide variety of indigenous languages with which Spanish has had contact. There are 25 indigenous languages in Guatemala, 2 in El Salvador, 8 in Honduras, 9 in Nicaragua, 6 in Costa Rica, and 8 in Panama.

This dialect is made up of Mexican (northern, central, and coastal), Mayan-Central American (Yucatan Peninsula, Chiapas, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua), and Spanish spoken by bilingual indigenous people (Nahuas from Mexico, Mayas from Guatemala and the isthmus of Panama, Boricuas from Costa Rica, and Ngäbe from Panama). Costa Rica shares elements with both, Caribbean and Central American dialects

Pronunciation

Mexican Spanish S, Z, C Pronunciation Example

Juan from Easy Spanish

- Seseo: pronouncing Z like an S, as well as the letter C when followed by an E or an I.

- casa = caza

- Sena = cena

- sima = cima

In the audio, Juan pronounces the same way the letters S, Z, and C:

- soy realizador audiovisual

- me gusta mucho el cine y el café de especialidad.

- Ceceo: pronouncing Z, S and the syllables CE and CI with the sound of a Z. This happens in Central America, especially in rural regions of Honduras and El Salvador.

- In the coasts of México and in Central America, the sound of the letter J and the syllables GE and GI is soft, like an H in English.

- cajón → cahón

- geranio → heranio

- girasol → hirasol

- Weakening the unstressed vowels to the point that they are sometimes dropped.

- oficina → ofcina

- nosotros → nosotrs

- entonces → ntons

- Widening stressed vowels.

- Turning a strong unstressed vowel (a, e, o) into a weak vowel (i, u) or sometimes just dropped when they are next to another strong vowel. This is called diphthongization and is associated with low-status groups.

- peor → pior

- aereopuerto → airopuerto

- Strong pronunciation of consonants. For example, many consonants often acquire a soft sound, especially when placed between two vowels. In the word dados, the first D is strong while the second one is soft. In this dialect, however, both D’s would sound the same.

- Pronouncing f with the lips instead of using the lower lip and the upper teeth when it is located at the beginning of a syllable. If it is followed by a U, it can even sound like a soft H. This is associated with low-status groups.

- afuera → ahuera

- fumar → humar

- fue → hue

These three sounds coexist in El Salvador and Guatemala. In regions with Mayan influence, the letter F is pronounced as P as the F sound does not exist in Mayan.

- Aspiration of the S when it is located at the end of a syllable.

- buenos → buenoh

- muchas → muchah

- más → máh

- Softening the LL/Y sound when it is placed between two vowels.

- tortilla → tortía

- hoyo → hoio

- Yeísmo: pronouncing LL as Y.

- llama = yama

- halla = haya

- llena = yenaOnly in two regions in Mexico – the Valley of Atotonilco and Orizaba – LL preserves its distinctive sound.

Use

- The pronoun tú is used as an informal you, to express closeness and familiarity, in Mexico and Panama, and sometimes in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. In Costa Rica this is every time more common but in Nicaragua, on the other hand, it is restricted to the literary language.

- The pronoun vos is used in Nicaragua and Costa Rica as an informal you. In Chiapas, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and the west of Panama, it is also used but in ways that are difficult to structure. In Guatemala, for example, when a man talks to other men, he may refer to them using vos, as using tú would be seen as “girly”. On the other hand, if a woman uses vos, people would think she sounds vulgar so they normally stick to usted.

- The pronoun ustedes is used for plural you.

- Preterite is used to talk about the recent past, just like in the rest of the continent.

- America: Esta mañana tuve un accidente.

- Spain: Esta mañana he tenido un accidente.

- Adding a final N when the plural form of the imperative ends with a pronoun. This is associated with low-status groups.

- váyanse → vayansen

- espérense → espérensen

- apúrense → apúrensen

- Adding a final S in preterite with tú.

- hablaste → hablastes

- comiste → comistes

- dijiste → dijistes

Sometimes the previous S is dropped.

- hablates

- comites

- dijites

Both phenomenons are associated with low-status groups.

- Doubling information to avoid ambiguity. This is not used by high-status groups.

- La tía de su mamá → Su tía de su mamá.

- Turning the pronouns lo/la into los/las to show that se is plural.

- Ya se lo dije a mis hermanos. → Ya se los dije a mis hermanos.

- Replacing imperfect subjunctive with present subjunctive.

- Le dije que viniera. → Le dije que venga.

- Lack of use of present subjunctive.

- No creo que venga. → No creo que viene.

- Using le as an intensifier, mainly in Mexico.

- Ándale

- Échale

- Híjole

- Órale

- Endings words in -ote, -ota, and -azo for augmentatives in México. Sometimes they also express dislike.

- grande → grandote

- casa → casota

The ending -azo is common when talking about blows.

- golpe → golpazo

- madrazo

- cabezazo

- codazo

- Endings words in –ito and -ita for diminutive. This is used for nouns, adjectives, gerunds, and adverbs.

- cerveza → cervecita

- chico → chiquito

- llegando → llegandito

- ahora → ahorita

- Ending words in -tico and -tica for diminutive when the stem of the words ends in T. This is done in Costa Rica and it is why they are known as ticos.

- rato → ratico

- gato → gatico

- puerta → puertica

Check out episode 42 of the Learn Spanish and Go podcast to listen to our interview with our Tica friend Carlota Morales to hear an example of the Costa Rican Spanish accent.

- Adding the prefix re- as an intensifier in Mexico.

- bien → rebien

- feo → refeo

- sabroso → resabroso

- Using adjectives as adverbs.

- huele mal → huele feo

- canta suavemente → canta suave

- llegó recientemente → Llegó recién

- Turning impersonal verb haber into plural.

- Había muchas personas. → Habían muchas personas.

- Hubo muchos problemas. → Hubieron muchos problemas.

- Leísmo de cortesía: to sound more polite, the pronoun le takes the place of lo or la when it refers to a person.

- ¿Lo/La puedo ayudar? → ¿Le puedo ayudar?

- Replacing the preposition en with a when using verbs of movement.

- La ropa se mete en el armario. → La ropa se mete al armario.

Vocabulary

This region is where Spanish has contact with the largest number of indigenous languages and all of them have some influence on this dialect. Let’s have a look at some of them.

- Nahuatl:

- chocolate

- coyote

- chile: chilli.

- tomate: tomatoe.

- aguacate: avocado.

- chicle: chewing gum.

- Mayan:

- agüío: a type of bird.

- cacao: cocoa.

- cachito: a little piece of something.

- chamaco: little boy or girl.

- chapín: Guatemalan.

- canche: blond, white.

- Mexican slang:

- chido: cool.

- wey: dude.

- no mames: no way.

Mexican Spanish Slang Example

Juan from Easy Spanish

Andean Spanish

Andean Spanish is spoken in the Andes and can be divided in four types: Coastal (Pacific coast of Colombia, Ecuador and Peru), Highland (Colombian-Ecuadorian, Peruvian-Bolivian, and Spanish spoken by bilingual indigenous people), Amazonian (Amazon territories in Ecuador, Peru, and Colombia), and Flatland (Bolivia).

Peruvian Spanish Accent Example

Pronunciation

- Seseo: pronouncing Z like an S, as well as the letter C when followed by an E or an I.

- casa = caza

- Sena = cena

- sima = cima

- Weakening the unstressed vowels to the point that they are sometimes dropped.

- oficina → ofcina

- nosotros → nosotrs

- entonces → ntons

- Swapping letters C, P, and T.

- septiembre → sectiembre

- aritmética → arigmética

- Pronouncing f with the lips instead of using the lower lip and the upper teeth. This happens in areas that are in touch with indigenous languages from Colombia, Hills of Ecuador, and some areas in Perú.

- afuera → aphuera

- fumar → phumar

- fue → phue

- Pronouncing LL and Y differently in Andean regions of Venezuela, Colombia, Perú Bolivia, Paraguay, northeast of Argentina with Guarani influence and border with Bolivia due to the influence of the Guarani of Paraguay and the Quechua and Aymara of Perú and Bolivia.

- llama ≠ yama

- halla ≠ haya

- llena ≠ yena

Use

Colombian Spanish “usted” Pronoun Example

Andrea from Spanishland School

- The pronoun vos is used as an informal you, to express closeness. In Ecuador the verb is conjugated as tú. The pronoun tú is used mainly in the coast of Colombia.

- ¿Vos tienes calor?

- The pronoun usted is used as a formal you but also, in Colombia and certain parts of Ecuador, it expresses the exact opposite: warmth and friendliness.

- Preterite is used to talk about the recent past.

- America: Esta mañana tuve un accidente.

- Spain: Esta mañana he tenido un accidente.

- Leísmo de persona: the pronoun le is sometimes used instead of lo or la. In this case, le is used also for feminine and inanimate direct objects, especially in Ecuador.

- Ayer vi a Juan y lo invite a la fiesta. → Ayer vi a Juan y le invite a la fiesta.

- ¿Viste a María? Sí, la vi. → ¿Viste a María? Sí, le vi.

- ¿Lavaste el carro? Sí, lo lavé. → ¿Lavaste el carro? Sí, le lavé.

- Loísmo: the pronoun lo replaces le, even when the object is feminine and plural. This is considered an incorrect use.

- Le llamé a Pedro. → Lo llamé a Pedro.

- La papa también la pelamos. → La papa también lo pelamos.

- Trea las velas para prenderlas. → Trae las velas para prenderlos.

- Dropping the final S in compound words when it is singular.

- sacapuntas → sacapunta

- abrelatas → abrelata

- Ending words in -ito, -ita, -ico, -ica for diminutive in Ecuador and Colombia. This can be applied to adverbs, demonstratives, quantifiers, and gerunds.

- aquí → aquicito

- esta → estica

- uno → unito

- corriendo → corriendito

- Using the verb dar as an auxiliary verb in Ecuador. The verbs botar, dejar, and mandar are also used this way.

- ¡Ábreme la puertita! → ¿Me das abriendo la puertita?

- Cocino por ti los domingos. → Te doy cocinando los domingos.

- The predominance of the form ir a + infinitive over future simple.

- Iré al cine con Juan. → Voy a ir al cine con Juan.

- Replacing pluperfect with imperfect.

- No había llegado María cuando nos fuimos. → No llegaba María cuando nos fuimos.

- Replacing imperfect subjunctive with present subjunctive.

- Le dije que viniera. → Le dije que venga.

- Replacing estar with ser in the Hills of Ecuador.

- Guayaquil está en Ecuador. → Guayaquil es en Ecuador.

- Dropping direct object pronouns.

- ¿Leíste el libro? Sí, lo leí. → ¿Leíste el libro? Sí, leí.

- Placing possessives after nouns.

- mi hija → la hija mía

- su casa → la casa de ustedes

- Adding muy to a superlative.

- muy rico, riquísimo → muy riquísimo

Colombian Spanish Accent Example

María from Español con María

Vocabulary

Here, two indigenous languages have a strong presence: Qechua and Aymara.

- Quechua:

- cancha: field.

- carpa: marquee.

- llucho: naked.

- yapa (Ecuador and Perú) or ñapa (Bolivia): addition.

- ¡achachay!: to express approval in Colombia, cold in Ecuador, fear in Perú.

- ¡atatay!: to express dislike in Colombia, nausea in Ecuador and Perú, and pain, especially from a burn, in Bolivia, Colombia, and Ecuador.

- Aymara:

- chipa: basket to carry fruits.

- chuto: uncouth.

- Andean slang:

- calato: naked, in Perú, Bolivia, and Chile.

- huachafo: corny, in Ecuador, Perú, and Bolivia.

- andinismo: climbing. This term is also used in Argentina and Uruguay.

- empamparse, empampanarse: to get lost in the pampas.

- Saying Don or Doña to show respect.

- Saying de repente to express possibility.

Tal vez no está aquí. → De repente no está aquí.

In the following audio, Andrea from Colombia tells us some of the most common words and phrases.

Colombian/Andean Spanish Slang Example

Andrea from Spanishland School

Austral (Rioplatense) Spanish

In Austral Spanish, also known as Rioplatense, we can distinguish the following varieties: Guarani (Paraguay and northeast of Argentina) and Atlantic (Cuyo, center and northwest of Argentina on one hand, and Buenos Aires with its area of influence and Uruguay on the other, also Patagonia with influence of Mapuche).

Pronunciation

- Pronouncing LL and Y as SH, as the S in Asia, or ZH , as the S in measure or usual. This is called sheísmo and zheísmo.

- yo → sho, zho

- pollo → posho, pozho

- Seseo: pronouncing Z like an S, as well as the letter C when followed by an E or an I.

- casa = caza

- Sena = cena

- sima = cima

- Widening stressed vowels.

- Weakening the S when it is located at the end of a syllable. It is sometimes dropped but this is associated with low-status groups.

- buenos → buenoh

- muchas → muchah

- más → máh

- Dropping the D and R at the end of a syllable.

- usted → usté

- cantar → cantá

- Dropping the D sound in between vowels.

- toda la vida → toa la vía

- cantado → cantao

- bebido → bebío

- Softening the sound of the letter J and the syllables GE and GI, like an H in English.

- cajón → cahón

- geranio → heranio

- girasol → hirasol

- Stressing unstressed pronouns.

- dígame → digamé

- ponérmelo → ponermeló

- Yeísmo: pronouncing LL as Y.

- llama = yama

- halla = haya

- llena = yena

Argentinian Spanish Accent Example

Diego Zacarias

Use

- The pronoun vos is used as an informal you. The conjugation is the result of dropping the I of the verb conjugated with vosotros. The pronoun tú is not used at all.

- vosotros habláis → vos hablás

- vosotros sabéis → vos sabés

- Preterite is used to talk about the recent past.

- America: Esta mañana tuve un accidente.

- Spain: Esta mañana he tenido un accidente.

- Replacing imperfect subjunctive with present subjunctive.

- Le dije que viniera. → Le dije que venga.

- Adding the prefix re- as an intensifier.

- bien → rebien

- feo → refeo

- sabroso → resabroso

- Endings words in -ito and -ita for diminutive, especially in words related to cooking.

- café → cafecito

- sopa → sopita

- Queísmo: the preposition de is dropped with verbs that require to be followed by de que. This is considered an incorrect use of the language.

- Me di cuenta de que no traje mis llaves. → Me di cuenta que no traje mis llaves.

- Estaba seguro de que vendrías. → Estaba seguro que vendrías.

- Adding the preposition de before que when it is not needed. This is called dequeísmo and is considered to be an incorrect use of the language.

- Es posible que venga mañana. → Es posible de que venga mañana.

- Doubling the direct object.

- Vi a tu hermana./La vi. → La vi a tu hermana.

- Invité a Juan./Lo invité. → Lo invité a Juan.

- Using adjectives as adverbs.

- huele mal → huele feo

- canta suavemente → canta suave

- llegó recientemente → Llegó recién

Vocabulary

Besides finding loanwords from indigenous languages – Guarani and Quechua – here we find as well influence from Italian, as since the middle of the 19th century and during most of the 20th century around 6 million Italians arrived. There is also Lunfardo, a slang that developed in the outskirts of Buenos Aires in the turn of the century and became popular through tango, crossing the barrier between social classes. Chile and Paraguay share a lot of these words.

- Guaraní:

- matete: confusion.

- Quechua:

- guarango: rude.

- tener cancha: to be an expert.

- pampa: flatland.

- sobre el pucho: immediately.

- Italian:

- capo: lider.

- laburar: to work.

- valija: suitcase.

- Lunfardo:

- cana: police.

- escabiar: to drink alcohol.

- farra: party.

- mina: woman.

- ¡che!

Chilean Spanish

Chilean Spanish has remained within its national boundaries, probably due to its mountains and its geographic location. Four divisions can be made: north (Tarapacáand Coquimbo), center (Colchagua),south (Penco), and souther-austral (Chilote on the southern Chilean islands of Chiloé Archipelago). The main indigenous language in this area is Mapuche in the south. In the north, a slight influence of Quechua can be found.

Chilean Spanish Aspiration of the S Example

Pronunciation

- Yeísmo: pronouncing LL as Y.

- llama = yama

- halla = haya

- llena = yena

- Seseo: pronouncing Z like an S, as well as the letter C when followed by an E or an I.

- casa = caza

- Sena = cena

- sima = cima

- Dropping the D sound in between vowels and at the end of a word.

- toda la vida → toa la vía

- cantado → cantao

- usted → ustéIf the D sound is before an R, it is sometimes pronounced as a hard H but this happens only when using the most informal way of talking, and is used mainly by low-status groups in rural areas.

- padre → pajre

- Aspiration of the S when it is located at the end of a syllable or in between vowels. It can sometimes be dropped but this is associated with low-status groups.

- buenos → buenoh

- muchas → muchah

- así → ahí

Listen to the way Karin pronounces the following:

- profesora de español

- algunas de las cosas que me gustan

- personas de distintos países

- Softening the CH sound, pronouncing is as SH. This is associated with low-status groups.

- muchacha → mushasha

- ocho → osho

- mucho → musho

- Softening the sound of the letter J and the syllables GE and GI, much more than the rest of the dialects.

- cajón → cahón

- geranio → heranio

- girasol → hirasol

- Dropping consonants at the end of a word.

- papel → papé

- cantar → cantá

- aman → ama

- usted → usté

- Weakening the R at the end of a syllable. It can be aspirated or even dropped.

- carne → cahne

- soltarle → soltale

- Weakening the B, D, and G sounds. The B is usually pronounced as V.

- había → havía

Use

- The pronoun tú is used as an informal you, but the verb is conjugated with vos.

- vos hablái → tú hablái

- vos tenís → tú tenís

- vos vivís → tú vivís

- The pronoun vos remains used in rural areas by low-status groups or to show discourtesy. The S in vos is aspirated.

- vos hablái → voh hablái

- vos tenís → voh tenís

- vos vivís → voh vivís

- Preterite is used to talk about the recent past.

- America: Esta mañana tuve un accidente.

- Spain: Esta mañana he tenido un accidente.

- Conjugating ser in two different ways for tú or vos.

- tú/vos soi

- tú/vos erís

- The imperative is used with tú, regardless of which pronoun is used.

- tú/vos habla

- tú/vos come

- tú/vos escribe

- Endings words in -ito and -ita for diminutive.

- cerveza → cervecita

- café → cafecito

- Queísmo: the preposition de is dropped with verbs that require to be followed by de que. This is considered an incorrect use of the language.

- Me di cuenta de que no traje mis llaves. → Me di cuenta que no traje mis llaves.

- Estaba seguro de que vendrías. → Estaba seguro que vendrías.

- Dequeísmo: adding the preposition de before que when it is not needed. This is considered to be an incorrect use of the language.

- Es posible que venga mañana. → Es posible de que venga mañana.

- Turning impersonal verb haber into plural.

- Había muchas personas. → Habían muchas personas.

- Hubo muchos problemas. → Hubieron muchos problemas.

- Replacing imperfect subjunctive with present subjunctive.

- Le dije que viniera. → Le dije que venga.

- Using le for both, singular and plural. Placing de N that marks the plural in imperative after the pronoun.

- déjenme → déjemen

- háganme → hágamen

- tráiganme → trágamen

- Using le as an intensifier, mainly in rural regions.

- caminen → caminenle

- apúrense → apúrenle

- Placing a definite article before someone’s name.

Vocabulary

These are some of the words you will hear in this dialect.

- Andean:

- aconcharse: to become marred.

- combo: punch.

- pisco: grape liquor.

- polla: lotery.

- Chilean:

- al tiro: immediately.

- bacán: fantastic, good, nice.

- cahuín: gossip.

- carrete: party.

- flaite: a member of the lower class associated with crime, a person that is not trustworthy, something of bad quality.

- fome: boring, graceless.

- la once: meal taken in the afternoon, between five and seven, and that usually consists of coffee, tea or milk and bread.

- paco: policeman.

- Mapuche:

- calcha: lock of hair.

- cancato: a type of fish.

- carchazo: slap.

- pichintún: a little of something.

- pololo, polola: boyfriend, girlfriend.

- Quechua:

- chascha: long, messy hair.

- chupalla: straw hat.

- encacharse: to dress up.

- pucho: fag-end.

- pupo: navel.

- Slang:

- ¿cachai?: do you understand?

- pues → po

- ya

Chilean Spanish Slang Example

Karin from Idioma Pro

Equatoguinean Spanish

Spanish is natively spoken on four contients, and Africa wouldn’t be on the list if it wasn’t for Equaltorial Guinea. Once a Spanish colony, Equaltorial Guinea is a small independent country located on the western coast of Africa.

Equatoguinean Spanish Accent Example

Monanga Bueneke

Check out our interview with Monanga Bueneke on the Learn Spanish and Go podcast to listen to “African Spanish” – an example of the Spanish accent in Guinea Equtorial.

Conclusion

This was an in-depth look at the main Spanish dialects around the world. Each of them has, of course, countless variations. Even in the same city, people will speak differently depending on their age, what they do, or who they are talking to. Although it may sometimes lead to innocuous misunderstandings – is the guagua you are talking about a bus, a baby, or a dog? – this diversity does not keep us from communicating effectively with each other.

Learn More About Spanish Accents:

DEVELOPING AN ACCENT IN SPANISH IS AN IMPORTANT PART OF ACHIEVING FLUENCY. IN THIS VIDEO WE’LL GO OVER THREE MAIN POINTS TO HELP YOU NOT SOUND LIKE A GRINGO: 1. WHY YOU SHOULD DEVELOP AN ACCENT IN SPANISH. 2. WHICH COUNTRY SHOULD YOU MODEL OR COPY? 3. TIPS TO HELP YOU START IMPROVING YOUR ACCENT TODAY.

Related Posts

Beginner Spanish Phrases Every Traveler Needs to Know

The Importance of Developing an Accent in Spanish (How to Not Sound Like a Gringo)

Different Ways to Say Dog in Spanish